My weblog ELECTRON BLUE, which concentrated on science and mathematics, ran from 2004-2008. It is no longer being updated. My current blog, which is more art-related, is here.

Fri, 30 Sep, 2005

The paint is just dry

My latest art effort for my upcoming show is done. It is called DECO FANTASY and it is acrylic on illustration board, 22 inches vertical 13 inches horizontal. It has plenty of brilliant colors and high contrast, because it is designed to go into a small, dark corner space in the exhibition area and in the dimly lit house of a possible buyer. I hope it can brighten up a New England winter. As far as I know, it has no political or social significance. Here's a view of it, fresh from the studio.

I have two pictures left to paint for the show, possibly three if I paint fast. I will be using airbrush for some of these next three. I hope that Fine Arts Galleries don't mind airbrush textures. I have no idea if they do, maybe airbrush is considered crass and "pop" rather than "fine." I know very little about the "fine arts" field in general, having been a commercialoid all my life. But I do know that no artists make any money in "fine art" so they have to be academics or teachers or something of that sort. Or perhaps, a "fine artist" could be like one of my favorite artists, Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte. He worked at commercial design and advertising jobs at least in the earlier years of his career. Since I cannot expect to have a "fine arts" career in which money would be made, I am happy to keep my day job, not to mention the samples of wine, cheese, and artisan bread.

Thick acrylic paint takes a long time to dry, so I had plenty of time to do physics problems while waiting for Deco Fantasy to become Deco Reality. I am currently working on old-fashioned high school problems about mechanical advantage, and am about to be introduced to the exciting world of loading ramps, winches, and gears.

Posted at 4:17 am | link

Wed, 28 Sep, 2005

Heavy Lifting

The physics problems I am doing now inspire me to shop for work boots. Heavy, black, waterproof, oilproof, steel-toed kickers suitable for an environment in which work like this is done:

"A set of pulleys operates a lever that pushes on a hydraulic press that operates another lever. To make the last lever arm move 12 centimeters, it is necessary to pull 15 meters of rope through the pulley…"

Actually, such things exist in the back of the gourmet store and I have used them, for instance the chain pulley that opens the garage door. You would think that signage in a gourmet store would be a genteel sort of affair, artistic ladies doing swirly calligraphy on lacy decorative tags for smoked salmon and petit fours. But my work often involves big flat boards, spray paint, suspension cords and chains, and power tools (though I don't operate the latter, due to safety restrictions). I have the opportunity to exert mechanical advantage (or be stuck behind a negative mechanical advantage) every day I work there.

Just as with my trigonometry problems last year, these simple machine problems bring with them their own vivid atmosphere. With trig, I was out on the ocean in the mist and sunlight, sighting with my instruments the angles of the landmarks by which I plotted my course. Here with machines, I am in a brawny industrial world of pulleys and winches and cranks and gears and bolts and hydraulic jacks. It is putting hair on my metaphorical chest. And I would much rather wear construction boots than tiny little fashionable sandals.

Posted at 4:16 am | link

Fri, 23 Sep, 2005

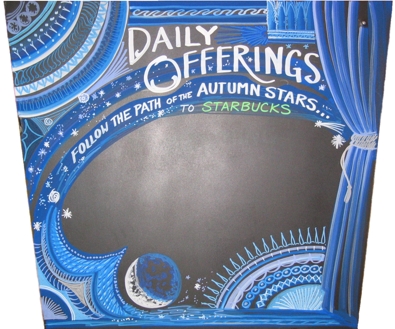

Autumn Stars of Coffee

I've been doing some nice art for Starbucks lately. I decorate the placard above the counter which advertises the "daily offerings" or coffee promotions of the week. I am not officially a Starbucks employee, which means that I can't be paid real money for it. But at each Starbucks I decorate, I get free coffee, as well as other merchandise if it is available. At this point in time I decorate four different Starbuckses in my area, once each season. I am currently changing the "summer" themes over to "fall." Thursday night I did this one which I am particularly fond of. It's based on nineteenth century printer's ornaments as well as celestial fantasy. The drawing is done in acrylic "poster paint" markers on a sturdy black-coated wood and metal board. The acrylic design can be removed with water and detergent when it's time for the next one. The empty area in the center is for the ad copy, which is done in water-soluble markers which can be erased with plain water and re-written at any time. It took an hour and a half, and a double tall cappuccino with almond flavoring.

Posted at 3:18 am | link

Tue, 20 Sep, 2005

I attempt to explain Quantum Physics to a Lady from India

Last night I had a telephone conversation with a lady who was visiting one of my artistic friends. My friend, an American, is married to a Parsi gentleman from India and her visitor was also from India, a Hindu lady whom she had known ever since their college days. She was in the USA to visit her son who worked in my general urban region. Somehow their conversation got around to me, my art, and my study of physics. The Indian visitor was most keen on meeting me but since she would be leaving the next day, I had no time to plan a journey over to her place so we had to talk on the phone. What did she want to talk about? She wanted to know about quantum physics, and thought that perhaps I could explain it to her.

Now this is a highly educated Indian lady who had been working in industry until her retirement, and her command of English was perfect, so it wasn't like I was going to have to struggle with language. But I had never before spoken with her, and she had been given the impression that I knew far more about physics than I actually do.

"But Mrs. N.," I pleaded, "I don't know anything about quantum physics. I may be studying physics, but I'm only at a high school level. And even Richard Feynman couldn't explain quantum physics. Why would I be able to?"

It turned out that our mutual friend had told her that I went to Harvard. That meant that I was smart enough to explain quantum physics. Never mind that in my days at Harvard I studied Greek and Latin Classics, not physics. Mrs. N. insisted. Could I possibly explain quantum physics to her?

Well, I decided to try, fool that I was. I have read plenty of non-mathematical books that try to explain it, with varying degrees of success. So I'm not totally unaware of the subject. For all that follows, I beg my Friendly Scientists' forgiveness.

"Well, Mrs. N., the first thing you have to be aware of is that things which look like they are continuous and unbroken, really are not. Water, for instance, looks like it flows like one continuous thing, but it's really made of zillions of little molecules of hydrogen atoms joined with oxygen atoms."

So far, so good. "So the entire material world is made of these tiny things. Not just molecules, but atoms, which are made of subatomic particles like electrons and neutrons and protons and some of these in turn are made up of quarks." (All of which Mrs. N. knew about.)

I continued: "Physicists in the early twentieth century discovered that things behaved very differently in the ultra-small world of subatomic particles, than they do in our ordinary world of larger mass and weight. In fact, quantum physics really only shows up in the world that is tinier than the atom, the subatomic particle world. Any other situation is too big to show it. Things with bigger scale conform to quantum mechanics too, but you can't see them because the effects are far too small, so things with bigger scale work the way our ordinary world does with momentum and weight and inertia and acceleration." (That's the stuff I am currently studying, that is, classical mechanics.)

She wasn't protesting, so I continued. "When these guys in the early twentieth century experimented with subatomic particles, they discovered weird effects. They discovered that the very act of observing something in the subatomic world, changed their results. How come? Because energy, like water, also looks continuous, but isn't. Radiant energy such as light is made up of untold zillions of little things called photons. We, or our instruments, can only see things because photons bounce off things and reach us. And they do it in discrete events, not a continuous stream."

Things were getting complicated for me, but I continued.

"Every time they did an experiment on something subatomic, they had to send photons to bounce off it, otherwise they wouldn't see anything. But every time the photon bounced off whatever they were trying to measure, it was so tiny that the photon changed it, either by making it "brighter," or by shoving it out of its track, or something else like that. So they were stuck. They could only measure something by throwing photons at it, and the photons changed what they bounced into, which is what you would see. So you could only get one measurement out of it, the one that you got when the photon hit, but anything else was changed. You could tell how fast some particle was going, but not where it was at the same time, 'cause your photon knocked it out of its track." (Where is Werner Heisenberg when I need him? Dead, and well beyond the reach of photons.)

Mrs. N. was listening patiently, as if I were actually making sense. "So everything we see," I continued, "is because photons reach our eyes, we can't see without light, and those photons are all little units, not a continuous stream. Now can we change things in our larger world just by observing them, the way they do in the subatomic world? No, 'cause everything in our world is just too big. Light won't push your car off course, the car is just too big. All it will do is light up your car so you can see it. (I neglected the fact that my own car is an Electron and is always stopped by the light of red traffic photons, as well as going on a curved path when it encounters a strong magnetic field such as a Starbucks Coffee shop or Borders Bookstore.) No matter how much philosophers or religious people try to make some sort of universal statement about human freedom and quantum uncertainty or the observer changing the system and thus "creating our own reality," this only works for really weentsy scale. It doesn't work for our size scale."

"Oh," she said.

"Did this make any sense to you? I told you I didn't know much about quantum physics. I'm not a physicist. I am just a beginning student."

"Well," said Mrs. N., "I didn't follow all of it, but thanks very much for explaining it to me."

I guess that was OK then. I asked her, "But how come you asked me about quantum physics? What got you interested in it?"

"I've been reading some books about science," she said, "and they talk about it."

"Which books?" I asked. "I was reading something by Deepak Chopra," she said, "and he talks about quantum physics."

Oh, gosh. I should have shut up right there, but I didn't. Deepak Chopra is a popular Indian personality who went from being a conventional doctor to promoting ancient Indian medical philosophy and Hindu teachings to the Western world, using the terminology of science to make it more palatable to us modern types. The trouble is that Chopra uses the theories of quantum physics in an inappropriate and even misleading way, for instance telling people that since the observer affects reality, you can, too, and you can create "miracles." And he calls his system "Quantum Healing" which doesn't mean much but sounds "scientific." It makes me mad, even though as a non-official scientist I don't really have the intellectual right to be mad.

"Mrs. N," I said, "getting information about quantum physics from Deepak Chopra is like getting information about evolution from a creationist. Just because he calls something "quantum" doesn't mean it has anything real to do with quantum physics. He consistently misuses physics to make his points. There are plenty other books or sites on the Internet which will honestly explain quantum physics and other modern science to you. I just don't trust Deepak Chopra at all."

Fortunately her friend intervened at that point so that I wouldn't go on with my rant. I really don't want to insult a nice Hindu lady I have never met. One of the things I have noticed about Indian religion in our era is that it is completely permeated with pseudo-science. Most of this happens in Hinduism but I have also seen it in some sectors of Zoroastrianism and Sufism. It is an amazing mixture that emerges from the modernization of a very, very ancient country that retains its traditions. Hindu philosophy, yoga, and world-systems are explained in terms of modern physics and chemistry, astrology is merged with cosmology, and Chopra's millennia-old Ayurvedic medicine is connected with biochemistry and neuroscience. Does any of it make sense? It does if you are Indian, but if you are an American like me, steeped in skepticism and the strict separation of religion and science, it makes my brain steam.

I must not have gotten too nasty, because Mrs. N. still wanted to talk to me, and she wanted to correspond, but she didn't have internet where she was in India. Could we correspond by mail? Post isn't too fast in India, she said, but with luck it would get there. I could send her references on modern physics. Any chance I would ever travel to India? She probably wouldn't be coming back to the USA because it is so expensive and such a long trip. I suppose I might get to India someday, but not anytime soon. I just hope I didn't cause a Quantum International Incident by my response to Mrs. N.

Posted at 3:43 am | link

Sun, 18 Sep, 2005

Physics Work

I have returned to the easy world of Barron's textbook for my introduction to "simple machines." Well, actually it's my re-introduction, because I first learned about this subject in seventh grade, in Mr. Cinkosky's general science class. That was 40 years ago. I am re-learning things about pulleys and levers and mechanical advantage and efficiency. None of these things has changed in 40 years. In fact, none of those things has changed in more than 2500 years. My "History of Science and Technology" book informs me that pulleys and other such simple machines were invented as early as the ancient Greek era if not even earlier by the Assyrians. And humans used levers in prehistoric times. They just didn't have Barron's "Physics Made Easy" to tell them how they worked.

As Barron's helpfully informs me, much of the hardware which surrounds me, from doorknobs to window blinds to pencil sharpeners to corkscrews, are simple machines which multiply my effort in order to get things done. "Without thinking about it," writes the author, "everybody uses a hundred simple machines everyday." As well as this complex one through which you are reading this. But the crank that turns this computer is metaphorical, not physical. It's all about work.

I live in an area where excessive work is not only not frowned upon, it is celebrated. Ever since I arrived here and discovered the urban work ethic, I have striven to equal it, since I don't want to feel out of touch or do less than the workers surrounding me. In fact, at first I wanted to get some fake cigarettes so I would look like I was smoking, since so many people around me smoked. But I came to my senses about that. Most of my co-workers smoke. Smoking is a sign that you work so hard and are under such pressure (or even danger) that you don't have time to think or care about your health, and you need that fleeting moment of pleasure and relaxation, like soldiers on the front line.

Working too hard is a badge of honor. I have long since gotten used to people describing their lives around here: it's hectic and crazy. These are not exceptional moments in those lives; they are the standard. In fact, if your life isn't hectic or crazy or overscheduled, there's something wrong with you. You are a slacker. So I have always thought that I don't do enough. My job is part-time (25 hours a week) but I go home and do more art and writing afterward, so it might add up to a proper 40-hour week. A real week's work in this area is over 60 hours, up until 80 hours or even more. Go, go, go! Be lucky you still have a job, since someone in India will do those 60 to 80 hours for half your pay.

I hear the same work ethic coming from scientists. They often talk about their "insane" hours or their all-night toil on research, writing, or experiments. They are under constant pressure to publish papers. They toil on tedious grant proposals and prepare lectures and correct exams. But in the case of scientists, it isn't for the money or the prestige. They say they work those insane hours because they love it, that their enthusiasm and fascination with the scientific quest drives them. Wow, I wouldn't work 80 hours a week on anything, even if I loved it. I guess I really must be a slacker. They think artists are privileged slackers anyway, because we play with paint and colors like children. It isn't, y'know, real work.

So I'm learning about the physics that makes most of the tools of my world work, from screwdrivers to mat cutters to palette knives to paintbrushes themselves. I'm trying to get more enthusiastic about this. It's where I am now, and I need to learn it. Those hardworking science pro's are pondering dark matter, cosmic strings, and braneworlds while I'm learning how nutcrackers and gears work. Wow, shovels and pitchforks! It's time to put in the fall bulbs anyway. Intellectual work does not follow the laws of physics and simple machines; it has no efficiency or mechanical advantage. It does, however, take up the hours, the long hours that show that I'm really doing the job.

Posted at 3:23 am | link

Fri, 16 Sep, 2005

Sisyphysicist, but physicists are not sissies

I have rolled the rock up the hill again, and finished my current series of problems in what I now know is called statics. I have analyzed the vertical and horizontal components of tension in cords and hanging blocks, sliding blocks, and objects pressed against the wall, along with the co-efficients of friction, which impedes motion. Many of those diagrams of multiple cords attached to weights in equilibrium reminded me of the classic humor-engineering cartoons of Rube Goldberg. Just add more and more levels of static and dynamic design, and you, too, can calculate how much force you need to fill a cup of water in 20 steps or more.

But I don't need to go anywhere far-fetched to find examples of the situations I've been working on. My work environment at the gourmet store is filled with signs and other weights hanging on just these types of angled cords and chains, as well as things held up against a wall. Gravity, support, pushing, pulling, and friction are everywhere. It's not just about brie cheese and endives and frozen jumbo shrimp. Every so often I have conversations with certain scientific or engineering-minded customers who know about my "secret vice." That was how I learned that I had been doing "statics," a word I had not heard before in the context of physics.

So I solved, and solved, and got my sines and cosines in the right directions. Sisyphus truly must have been a physicist in his own mythical time. I don't know whether I will remember all of this, but I think that if I remember to get the correct vertical and horizontal numbers first, then some of it will come back to me when I am hanging that sine, or rather sign. But the only rolling rock I can really appreciate is this one.

Now it's back to moving objects, Newton's laws, and a whole load of stuff about momentum. Much of this I have done before, so maybe the review won't take so long. But I don't count on it. Oops, there goes the rock down the hill again.

Posted at 3:33 am | link

Wed, 14 Sep, 2005

Sisyphus on the inclined plane

The ancient Greek physicists already knew these problems well. Problem 4.40 in the old scroll: Sisyphus rolls a stone up an incline of 20 degrees. The rock weighs something (in whatever ancient Greek weight units). The coefficient of kinetic friction of the stone against the incline is (something). What is the magnitude of Sisyphus' pushing force, what is the "normal" force of the rock against the incline, and how long will it take for the rock to roll down the incline, as always, just before Sisyphus can get it to the top. And how long will Sisyphus have to do this?

I knew that my labor on mathematics and physics would be, uh, of mythical proportions when I determined to do it the right way i.e. mathematically, back in Year 2000. I could have done what many others do, and just read books written for the popular market filled with colorful slick illustrations, accessible explanations, and nary an equation to be seen. I am constantly aware that I am going "against nature" by doing this study. Other women my age are doing appropriate things like scrapbooking and knitting.

I don't have that wonderful easy facility and talent possessed by the young, active, vital physicists who write the blogs I read. Math must come as easy to them as drawing does for me. But despite the platitudes I constantly hear about art and physics being similar, they are NOT similar in most ways. There is hardly any symmetry (as I remarked early on) between the two fields of human endeavor. Physicists can do art or music, even to a professional level, as well as lots of rugged athletic and sporting activities such as biking, long-distance running, and mountain climbing. But it is very rare for an artist to do math or physics at any level, and I don't know too many physically rugged artists. Most of my fellow artists simply cringe when I mention math and physics, and tell me how bad they are in it. Well, so am I. So an important part of my project here is to go against nature and do what few artists ever succeed in doing. Hence, my slow, slow, bit by bit journey through high school physics I should have learned 35 years ago.

Even at my best cognitive level, that is, un-fatigued or un-pressured, I know that in a few weeks I will have forgotten the material I am so painstakingly learning now. I will have to learn it again, or at least review it again. For instance, if someone now were to give me a test in, say, conic sections, I would seriously fail it, especially if the test were under pressure. I hold these science types in awe for having withstood twenty years of intense study, having taken and passed tests under all sorts of adverse conditions, not to mention the social pressures of being a graduate student under withering competition.

Why, then, do I continue to do this? Why not just make pretty and rather superficial paintings incorporating "scientific" themes and forget about those equations with the sines and cosines and coefficients of friction? Because I believe that if I am to truly prove my point and do what I challenge myself to do, I must not take shortcuts or slack off or fake it at any point. I need the tedious, boring, repetitive, mathematical and slow background before I do anything more. It all builds on these foundations. But the work sometimes seems to make no net progress. I roll that rock up the hill every time I go through a set of physics problems.

Posted at 3:50 am | link

Sun, 11 Sep, 2005

Distracted by Baseball

No Blue Electrons have come your way for a few days, because I have had the fortune to attend two major league baseball games in two days (at the same place), a concentration of big league action that I might never experience again. My first night was sponsored by Trader Joe's, as an outing for "crew" members, and I attended along with eleven other co-workers. The second night I took the place of a spouse who could not attend; since the couple had a pre-paid game plan, I was invited to come along instead.

Since these games were National League, I approached them with indifference. As an American League fan I had little knowledge or interest in what sports journalists call "the senior circuit." But I was moved to root root root for the home team, and in my non-Fenway baseball attendance, so far I am one and one. The first night, the home team lost in a draggy game, but the second night, the home team came from behind to win a thrilling contest. I was delighted, and overfed with popcorn. It wasn't Fenway, with the city lights, the Wall, and the immortal Citgo neon triangle, but it was baseball, and that's what counts.

My friend on the second night is an anthropologist, professor at a local college. Every year, she invites me to speak to her introductory anthropology class on comparative religion. It was fun to sit at a baseball game with an anthropologist as she explained why various players do a series of rituals before they come up to bat, or pitch, or even take their position in the field. According to her, the amount of ritualizing is proportional to the lack of control a player (or anyone) has over his/her environment and fortunes. In this view, then, an outfielder, who seems to have less stress in his fielding and more time to find the ball (unless he's Manny Ramirez), would do a minimum of ritual. But a batter who was facing fastballs at over 95 miles an hour would do much more. An example of this would be ex-Red Sox Nomar Garciaparra's obsessive glove-twitching before he steps up to the plate. The most ritualizing, then, is done by the fans, who have no control whatsoever over what happens down on the field. A stadium full of ritually garbed fans, chanting and waving, is an anthropologist's delight.

And of course baseball is also a joy for the would-be physicist and mathematician. The trajectory of the ball, especially on a night without much wind, is clearly parabolic, though I had no way of knowing how fast it was going as it left the bat. (R.K. Adair, in THE PHYSICS OF BASEBALL, gives a sample velocity of 110 mph at a 35 degree angle, for a home-run-length hit.) Adair stresses that air resistance must be factored into every hit, no matter whether there is wind. Many years ago, I drew cartoons of space-suited astronauts playing baseball on the moon, and I'm sorry that they never got to do it to see how far a ball would go in a vacuum with one-sixth Earth gravity.

Baseball is a treasure of mathematical symbolism. Just the squareness of the field is enough to lead into Pythagorean speculation. The four-ness of the bases is set off by the perfect square of the nine players and the nine innings. The National League is here mathematically superior to the American League which has adulterated the perfect square with the tenth man, the "designated hitter." The four-ness of balls for a walk is played against the three-ness of strikes for a strikeout. These numbers are only the simplest, most obvious elements of a game filled with sacred numerology.

As the paint dries on my current project, I continue to clank along on those physics problems about ropes and blocks and inclined planes and cranking pulleys. The graphs that try to illustrate the vertical and horizontal components of motion up or down an inclined plane do nothing for me. I have never seen one that made sense to me. So, rather unscientifically, I must take it on faith that one direction comes from the cosine of the incline's angle and the other from the sine. In these problems, my artistic intuition does not serve me at all, but misleads me. If I were in a class having to do these problems, I would already be helplessly behind the group, having been lost somewhere down at the bottom of the incline with a very high coefficient of friction.

Posted at 3:33 am | link

Fri, 02 Sep, 2005

Physics Inspired Art

When I first got into studying math and physics, just about every one of the people I talked to about it said, "You'll get artistic inspiration out of it and make new, mathematical and physics-inspired art!" Sure, I expected that I would, but that was not why I am studying math and physics. I have been doing geometric and mathematically inspired abstract art for most of my life, but only in miniature and rarely, if ever, shown in public. But now, due to some innovations in technique and materials which I talked about earlier, I'm able to make these geometric abstractions larger and turn them into real pieces that can hang on a wall.

So here's the second of my "New England" series. It's 20 inches square, acrylic on canvas, catalogue number 925. The title is UNIVERSE DETECTOR, which I will explain shortly. I had quite a number of technical difficulties with the piece, including leaky masking tape, uneven surfaces, sticky paint that wouldn't dry quickly, and tiny bugs getting onto my freshly painted surface. That's what happens when you paint in summertime. Well, now it's done and here it is.

The interlocking, more or less concentric squares in layers are inspired by the cross-section construction of the great particle detectors at accelerators like SLAC, Fermilab, and CERN. I know that these detectors are cylindrical and not square, but it's the concept that counts. In the detectors, layers of sensitive material, often huge and heavy stuff, are built up around the collision point, with the purpose of catching the tracks of the myriad particles that blast out of the colliding beams. Sometimes, interesting and unusual particle events happen, which the computers are programmed to intercept. There may be billions of collisions a second but the electronic sifters in the detector find only the ones that are unusual and worthy of study. Some of these are not just single particles, but "jets" of particles which have a distinct signature which often means that something fundamental like a quark has been smashed.

There are even some way-out theories which propose that particles created in these collisions can disappear into other universes. Sometimes a particle disappears and the physicists have no idea where it has gone. Mostly it turns out that the wayward particle escaped out a tiny gap left in the design, but other times, it just disappears. Did it go into another universe? This is why I called my painting UNIVERSE DETECTOR. You can see three distinct blue jets which means that our beams have hit a quark or some other ultimate particle dead-on. The beam collision is at the center, and the lines of blue and white denote particle trails. It's sort of like the comic book version of accelerator physics.

As an artist doing physics-inspired art, I confess that I have a major case of "physics envy." I can make any number of pictures that illustrate physics events or mathematical designs, but in doing so I am not really doing physics or mathematics. It is sort of like being a high-class fan. I can listen to the music but I can't ever play it myself. Just as I heard that my math and physics study would transform my art, I've also heard, from some of the scientists, that my art might help promote science by making it "visual" and "beautiful," and inspire young people to go into the field. Well, thanks, I think; it's still my lot to illustrate the adventure but not to have it myself. It's not like I would ever really be able to smash atoms or theorize about quarks or dark matter, since after five years I'm still working on rudimentary high school physics and math. Again, as my friendly advisers say, "You're so talented! You should do what you're best at!" Don't worry, guys, I won't stop doing art, including the geometric stuff (especially if it proves to be sell-able). But my physics envy, and my need for challenge in my life, drives me to do something I am not best at.

Posted at 3:45 am | link

Thu, 01 Sep, 2005

The Drowned World

I finished a painting yesterday, and was going to show it to you, but I don't have the heart for it after watching and reading about the destruction of New Orleans and the adjacent Gulf Coast by Hurricane Katrina. The places that are now heaps of wreckage sunk in polluted water are places that I marveled at just two years ago when I visited them on one of my road trips, in the summer of 2003. Ironically, I spent my only full day in New Orleans during a tropical storm, named "Bill," who I guess was Katrina's milder elder brother. I wandered through the streets of the French Quarter in heavy rain and blustering wind, swathed in rain gear, while tourists, hoping for sun but caught unguarded, wore what amounted to large colorful plastic trash bags printed with the name of their hotel or tour group.

I remember New Orleans, then, under heavy storm conditions, where some of the streets were already flooded and electric power was intermittent in many areas. Even so, I managed to shop, and dine in restaurants, and even draw a picture from inside a restaurant with an open side to the street, while the rain poured down. You can see how I tried to graphically convey the drenching rain with vertical pencil streaks. I remember begging the restaurant people not to close the panels that would wall off the interior space from the street, until I had finished, even though moist gusts of wind were wetting the tables. Now I wonder whether that restaurant even exists any more.

I had a "been there done that" feeling when later that year, my own neighborhood was struck by Tropical Storm Isabel, and we were without electric power for three days. Just yesterday, the outer remnants of Katrina passed over my area, dark low clouds racing quickly over the twilight earth, blustery winds agitating the late summer trees. There was lightning to the west, but no storm overhead; I heard later that there had been a tornado about thirty miles west of my location.

But any inconvenience I have experienced with tropical weather is nothing compared to the suffering of the residents of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast that I see on the TV news. And yet I guess it is evidence of my own insensitivity that I think less about human suffering than literary references. One of my favorite authors (at least with his early works) is the British science fiction/experimental fiction author J.G. Ballard. (I am purposely not including a link because some of my more sensitive readers may be disturbed by Ballard's language and more recent work.) During the 1960s Ballard wrote a series of "eco-disaster" science fiction novels, in which scientifically implausible but vividly described horrors are visited on our planet. His THE DROWNED WORLD, published in 1962, is set on an Earth where global warming has gone completely out of control, the temperate zones have become a tropical wasteland, the polar icecaps have all melted, and most of the world's coastal cities are under water. In 1966 he published THE WIND FROM NOWHERE, one of my favorite disaster books, in which a global hurricane of impossible speed and proportion grinds most of the civilized world into powder, while the pitiful survivors (if only short term, given the destruction of most of Earth's food-producing ability) huddle underground in subways, garages, and tunnels.

I thought of Ballard's disasters when I watched the wind from nowhere (well, not really nowhere) destroy the lush Gulf Coast. And now, the helicopters hover above the drowned world, and the salvage boats move through the waters of doom, trying to save the pitiful survivors. Ballard must be watching with great interest, as he is fascinated, even stimulated by horrific scenes like these. I am not so "experimental" (read: obsessed with destruction, mutilation, and monstrosity) as Ballard and other writers like him, so I will refrain from making any further comments and get back to the things which I can manage to do in my own little dry and orderly world. I'll show you my new painting in my next entry.

Posted at 3:47 am | link